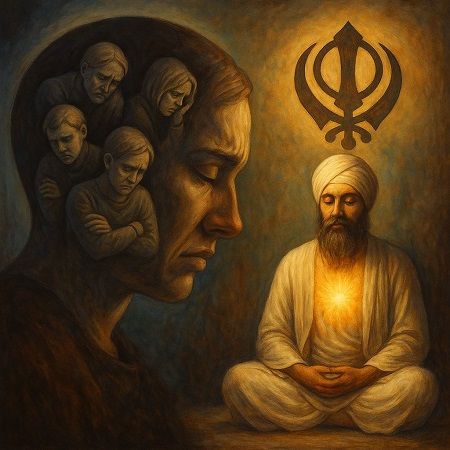

The Five Thieves as Parts: A Compassionate Approach to Sikh Inner Work

- Everything IFS

- Nov 29

- 3 min read

Updated: 3 days ago

In Sikh teachings, the Five Thieves,

Kaam (lust),

Krodh (anger),

Lobh (greed),

Moh (attachment), and

Ahankar (ego),

are described as forces that rob the soul of peace and pull the mind away from the Divine. For centuries, seekers have been taught to watch them, restrain them, and overcome them. But what if, instead of waging war against these inner forces, we learned to listen to them with compassion? This is the heart of the Internal Family Systems (IFS) approach, to see every inner struggle not as an enemy but as a part of us that longs for healing and understanding.

IFS teaches that within us live many parts, inner energies that carry emotions, memories, and beliefs from our life experiences. None of these parts are bad. They all began with a positive intention: to protect us, to help us survive, to make sense of pain. In the same way, Sikh wisdom reminds us that even the Five Thieves arise from the same Source; they are simply distortions of divine energy when it loses touch with Naam. What we call greed or anger is often love or strength twisted by fear.

Kaam, the thief of desire, may seem like temptation or craving, but beneath it is often a longing for connection, warmth, and intimacy. It becomes distorted only when it forgets its sacred root, love itself.

IFS would invite us to sit with the part of us that desires and ask, gently, what are you truly seeking? Sikhism echoes this through Simran, the remembrance that restores the heart’s hunger into divine union.

Krodh, the thief of anger, often emerges when we feel unheard, dishonored, or powerless. IFS teaches us to turn toward this part, not suppress it, to listen beneath its fire for the boundary it’s trying to protect.

Sikhism offers a similar path: when anger is met with Naam, it is purified into courage and righteous action rather than destruction. The fire becomes light.

Lobh, or greed, often grows from an inner part that fears scarcity, the belief that there will never be enough love, safety, or belonging.

Sikhism teaches that contentment (Santokh) is the true wealth.

IFS helps us reach that same freedom by helping the fearful part trust the Self, the inner calm presence that knows abundance is already here.

Moh, attachment, is not evil; it is love that has lost its grounding. It clings because it fears loss.

Sikhism teaches detachment not as rejection but as remembrance, to love deeply without forgetting the Divine.

In IFS, when we listen to the part that clings, it can release its grip and rest in trust, knowing it is held by something larger than itself.

And Ahankar, the thief of ego, is the part that tries to protect our identity, our dignity, our sense of self-worth.

Sikhism calls us to surrender ego through humility and service, reminding us that all glory belongs to the One.

IFS teaches the same truth in psychological form: when the Self leads, the ego no longer needs to shout. It can rest, knowing it is safe in the wholeness of the Self.

When we see the Five Thieves through this compassionate lens, they no longer appear as inner enemies to be conquered, but as misunderstood protectors longing for redemption.

Sikhism and IFS both affirm that transformation happens not through punishment but through love. When we meet each thief with awareness, presence, and compassion, it returns home, its distortion dissolves back into divine harmony.

Healing, then, is not a battle. It is a remembrance. It is the realization that everything within us, even our shadows, can be turned toward the Light.

Comments